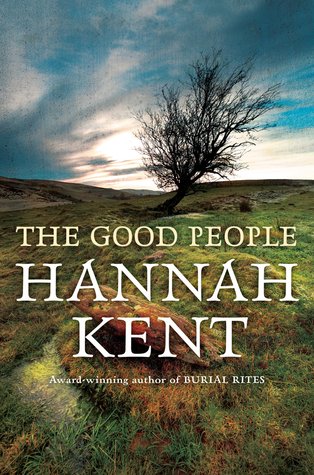

The Good People is set in an isolated village in Kerry, about ten miles from Killarney, in the years 1825 and 1826. It begins with the sudden but seemingly gentle death of Martin Leahy at the village crossroads, the place where traditionally suicides were buried. From the start, it is clear that this is a book immersed in portents, folk beliefs and superstitions.

Martin’s wife, Nóra, is left to struggle with their small holding and to care for their grandson, Micheál. Micheál is the four-year-old son of their dead daughter. He cannot walk or talk and has no control of his bodily functions, although for the first two years of his life he appeared to be a normal happy child. He is a screaming hungry burden that Nóra hides from her neighbours. When she engages fourteen-year-old Mary Clifford as a servant, Micheál’s his care falls mainly to Mary, especially at night when Nóra often takes to her bed with a jug of poitín. Life in the village is a struggle with hens not laying and cows failing to give milk, and whispers about the source of these problems swirl about Nóra’s household. As medical help has failed, Nóra turns to Nance Roche, the bean feasa or wise woman. Nance exists at the margins of village life, assisting at births and keening at wakes and funerals. She is the usual recourse of local people unable to afford the cost of a doctor with her knowledge of herbs and cures and her connection to the supernatural world, the eponymous Good People. Under Nance’s influence the notion, already hovering in Nóra’s mind, takes root that Micheál is not her grandson but a changeling.

Kent captures both the natural world and the atmosphere of the inward-looking village perfectly. The villagers themselves, their motivations and flaws are believable, running across the range of human types. The tenuousness of the life of a tenant farmer in Ireland at this time is grimly described, where the death of a husband, or even a cow failing to give milk can lead, in the end, to eviction and dispossession. It is into this world, twenty years later, that the great starvation arrived with the blight that caused the failure of the potato crop. Starvation and dispossession were the fate of people such as the characters that populate Kent’s novel.

Kent also touches on the politics of the period but it is so lightly done that I suspect that readers without a basic grasp of Irish history will miss it, seeing Fr Healy merely as a rigid grasping priest and neighbour Seán Lynch as a thoroughly unpleasant violent man. Both men, despite their character flaws, are looking toward a more modern, freer Ireland. The pennies that Fr Healy is collecting are not to line his own pocket but are the penny a month subscription to the Catholic Association, often collected by the parish priest, as part of the campaign by Daniel O’Connell for Catholic Emancipation which was the beginning of the end for the disabilities Catholics had laboured under since the 17th century. I was disappointed that these two characters were not more nuanced and were the two most unpleasant in the novel.

The Good People is beautifully written in lyrical prose. It is replete with Irishness from the many Irish words woven into the text to the superstitions and folk practices that seemed to govern nearly every aspect of daily life. The wealth of superstition in this corner of Kerry was the one element that I found most difficult to accept in The Good People. It is as if the characters follow almost every form of Irish folk belief that ever existed; my understanding is that often folk beliefs are quite local so while there would have been some deeply held beliefs, there usually would not have been so many. And while we do have a spectrum of attitudes within the book from Nance Roche’s total immersion to Fr Healy’s cold modernity, the majority of villagers huddle at the Nance Roche end of the scale. Yet it is people such as these who took themselves halfway around the world to America and to Australia both before and after the Great Hunger. My own great great grandparents, Patrick and Mary Connor of Killarney, brought their young family to the infant colony of South Australia in 1840 and seem not to have passed on any of these beliefs to their children. Other than Fr Healy and Seán Lynch, I cannot see any of the superstition-burdened characters in this book having the strength to throw over the weight of these beliefs and travel towards new horizons.

That said, The Good People is definitely a great read that totally immerses the reader in another time and place. Although it does not have the sense of total hopelessness of Hannah Kent’s last book, Burial Rites, I do hope that her next offering is a little brighter.

A review from the Irish Times can be found here and a lighthearted discussion of the Good People in modern Ireland here.

A good review, Catherine, and very helpful – thank you. I’ve had this on my Kindle for ages but haven’t got around to reading it. I’m not sure it will be quite my cup of tea, with all that superstition, but I thought Burial Rites was terrific, so I might give this one a go too. Really interesting for you that your forebears came from Killarney!

LikeLike

I didn’t like Burial Rites much but I thought this was brilliant. I was especially pleased to see that the political background was there as well.

Killarney is beautiful. We visited Ireland a couple of years ago and as we drove out of Killarney, I wondered how they felt as they left – there would have been sadness but excitement too. And with all my Irish forebears, their lives and those of their children were so much better than ever could have been hoped for in Ireland. I have great-great grandparents from Tipperary, Kilkenny and Cork, as well as a lot of English, mainly on my father’s side – Gloucestershire, Worcestershire, Shropshire and Staffordshire and a number of them were sent for their country’s good!

LikeLike

Pingback: 2018 – A Year of Reading | Catherine Meyrick

Pingback: Openings | Catherine Meyrick

Pingback: In my beginning is my end? – Opening and closing lines | Catherine Meyrick