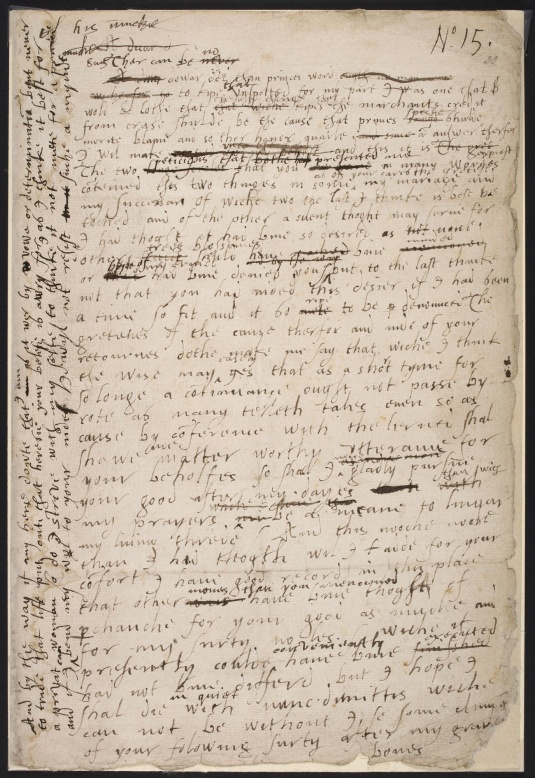

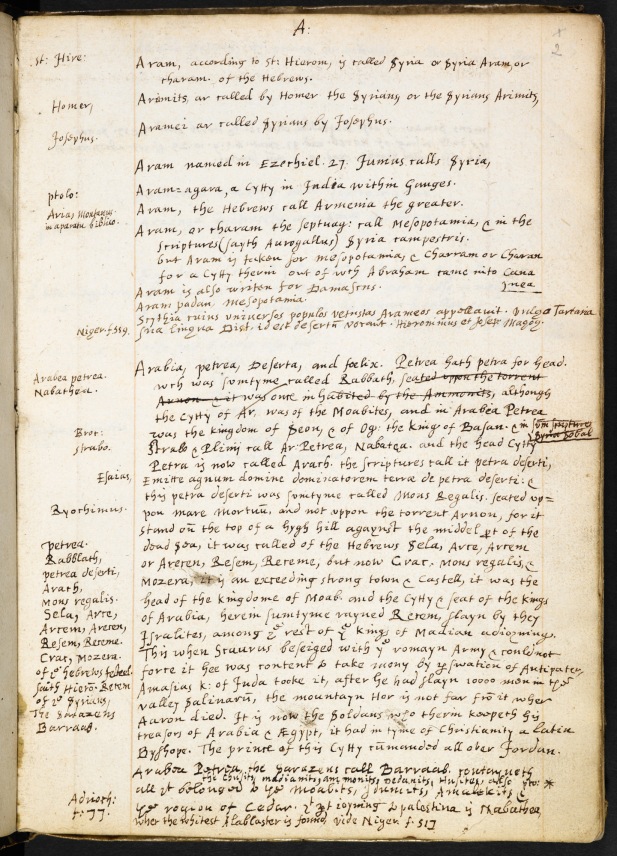

Yesterday was National Handwriting Day in a number of countries and wonderful images of pages handwritten by various people from the past were floating around the internet. One was the the draft of a speech given by Elizabeth I to Parliament on 10 April 1563 responding to a House of Lords petition urging her to marry. Most of those who commented on this image pointed to the deletions and replacements within the text showing how carefully Elizabeth chose her words and phrases. It definitely shows this and the genius that was Elizabeth I – no hired speechwriters for this great queen. But what struck me was the clarity of her hand. As someone who has spent countless hours transcribing records, from a complete set of Worcestershire parish records to all manner of convict records, a clear hand is an absolute joy. Several other examples of handwriting from the late 16th century appeared yesterday showing the same clarity.

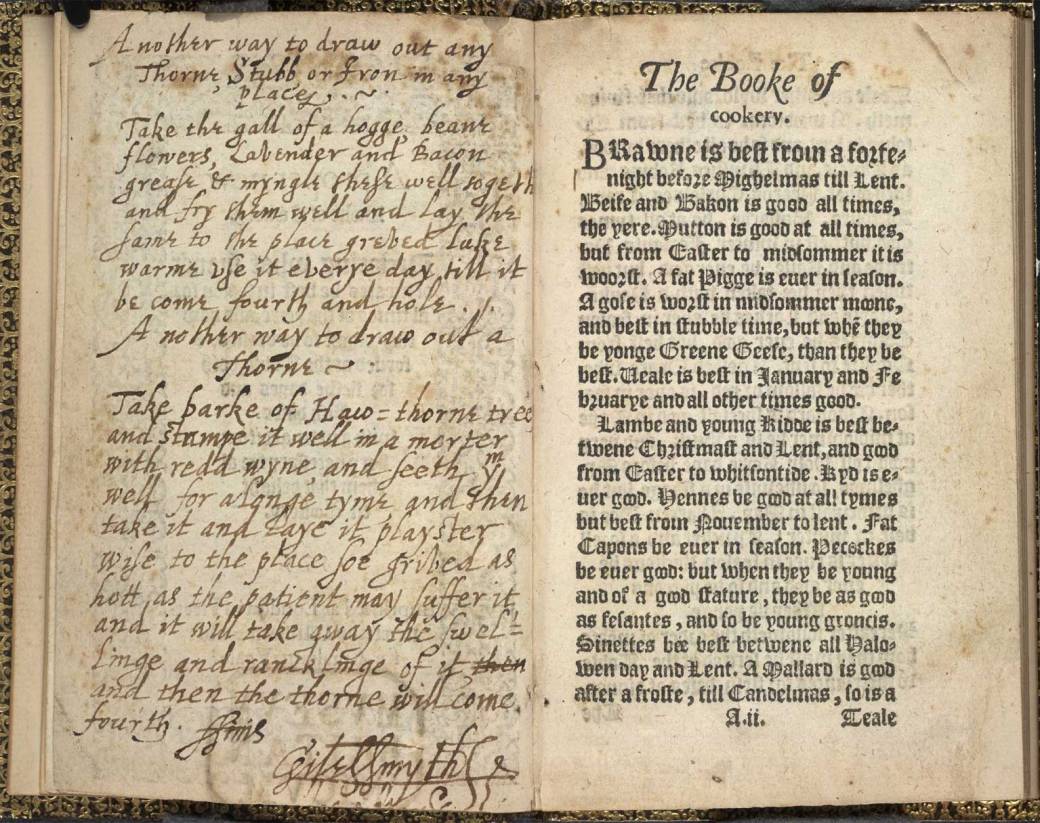

The first is written on a blank page in a printed recipe book and describes two methods for removing a thorn from skin.

The second, a page from a notebook written by Sir Walter Raleigh between 1606 and 1608 during his imprisonment in the Tower of London on charges of treason.

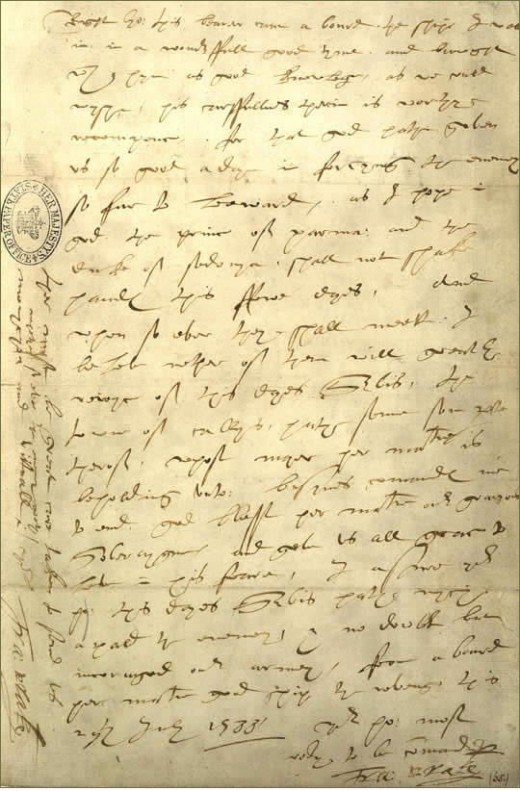

I was starting to form the view that handwriting was a skill well taught in the 16th century until I stumbled across this letter from Sir Francis Drake to Sir Francis Walsingham dated 29 July 1588, written on board Drake’s ship the Revenge after the battle of Gravelines. It is every bit as bad as any 19th century chook scratchings I have struggled with.

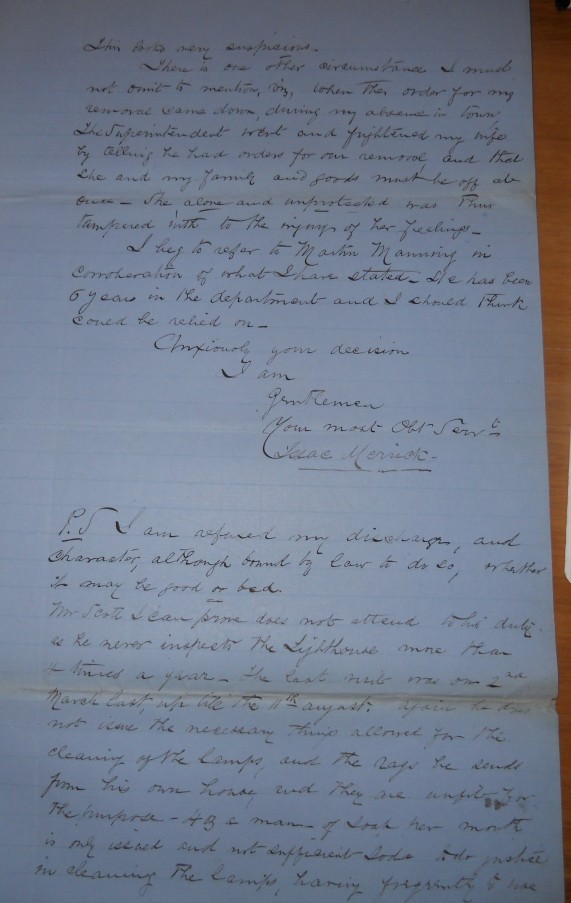

While it is amazing that these images are so easily accessible to us in any part of the world, there is a special wonder in being able to hold in your hand a document from the past, to know that you are touching the same paper held by those who lived so many centuries before. One of the greatest thrills of my family history adventures was to hold a letter signed by my great great grandfather, Isaac Merrick, in response to his dismissal from the Bruny Island Lighthouse by John Scott in 1875. Scott had described Isaac as a ‘lazy skulker’ and considered Isaac, his wife Margaret and eldest son John insolent. The bulk of Scott’s complaints regarding insolence centre around Isaac and Margaret’s behaviour at the time of the accidental death of their two year old daughter Christina in March 1875 and tell us more of Scott’s insensitivity and pomposity than they do of the character of Isaac and his family. Scott also had form in calling for dismissal of assistants who annoyed him. I do not believe that the letter itself was written by Isaac but he most certainly signed it and his signature is firm and well-formed. And while the construction of the letter was not Isaac’s, the sentiment behind it was his, and the sense of injustice at his treatment. This same sense of injustice can be found later in the letters his son John (my great grandfather) wrote in highly coloured prose to Tasmanian newspapers and was, no doubt, part of the reason for his involvement with the Labour Party in Tasmania in its formative years.

Final page of Isaac Merrick’s letter to the Hobart Marine Board in answer to Lighthouse Keeper John Scott’s complaints. (MB2/5/1/26 – Bruny Island 1 Jan 1872 to 31 Dec 1882)

The urge to touch is there with any of these documents, to connect to those people of the past who had written them. In 2012 the National Library of Australia exhibited a collection of handwritten documents called Handwritten: ten centuries of manuscript treasures. This exhibition included items such manuscript copies of Virgil and Dante to letters written by Machiavelli and Erasmus on to Simón Bolívar and Florence Nightingale as well as handwritten music by Handel, Mozart and Beethoven among many others. Of course all were displayed behind glass but there were moments where I wished I had the power to pass my hand through glass and touch the written words. The urge was strongest with two letters, one written in 1532 by Martin Luther, the man who inhabited my head for nearly a year in the late 1970s when I studied Reformation History. The other was a report to the Commissioners of the Navy dated 1776 by James Cook, the greatest of all mariners.

Perhaps while the eyes can deceive, touch can give us a truer sense of the past?

Reblogged this on From 1 Blogger 2 Another.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for the share.

LikeLike

These are all fantastic documents, thank you so much for sharing!

LikeLiked by 1 person

And there are so many more out there. It is just amazing the access we now have to things that would otherwise have been buried in archives thanks to digitization and the internet.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes certainly! Digitisation has certainly enriched historical research

LikeLiked by 1 person