‘A past that only consists of the artefacts is like a skeleton unearthed in an archaeological dig. Where is the flesh and blood? Who were the people? What did they feel? Where have they gone?‘ (Ancestry p.1)

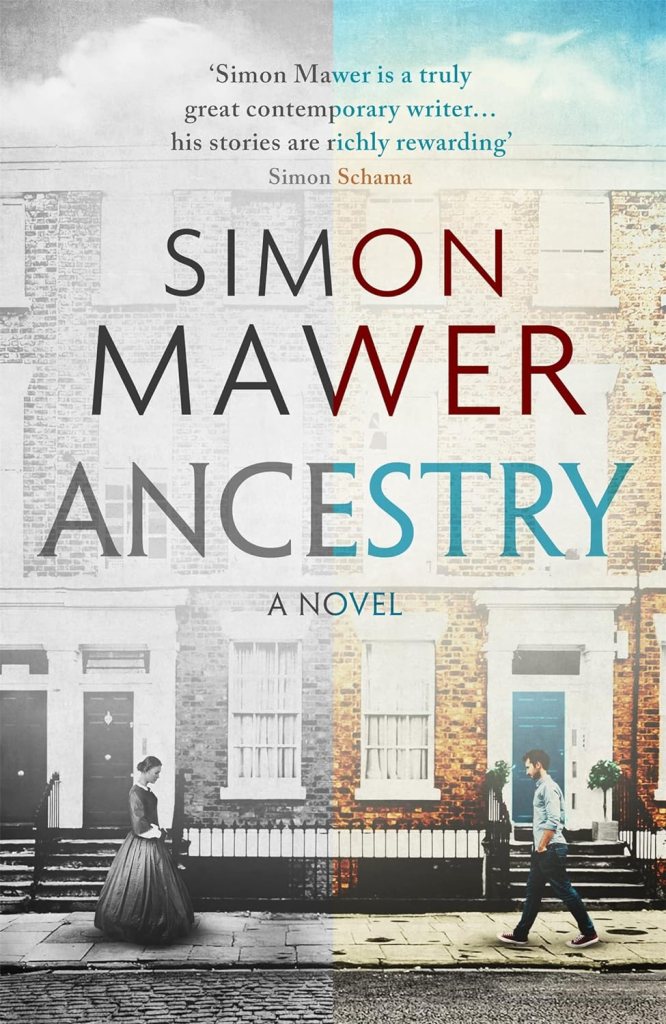

In Ancestry, Simon Mawer imagines the flesh and blood of two sets of his great-great-grandparents, ordinary people from the struggling working classes. The vicissitudes and sorrows of their lives, as well as moments of joy and achievement, are brought to vivid life in this meticulously researched novel.

The first third of the novel is taken up with the story of Simon Mawer’s maternal great-great-grandparents, Abraham Block, a seaman from Kessingland on the Suffolk coast, and the woman he married in London, Naomi Lulham, a seamstress from Hastings. Both had left their homes seeking a broader life with more opportunities than their home towns offered, Abraham arriving in London in 1847 and Naomi in 1849. Their lives, both before they met and together, show clearly the poverty endured by so many ordinary people, the accommodations forced on them, the injustices of a society that views some lives as of less worth than others, and the precariousness of life itself at this time. The lives of seamen, particularly those on ships that travelled abroad, and their families are evoked in detail as are the places where they lived such as parts of London in the 1840s and 1850s.

For two hours she walks the length of the street, pushing past the pedestrians, risking her life crossing from one side to the other … The city seethes around her, ripe with the stench of horse piss, loud with the rumble of iron-shod wheels. (p.83)

And when Abraham and Naomi’s lives have been told, we are given a brief glimpse of the lives of their descendants into the twentieth century.

Mawer does the same for the descendants of his paternal great-great-grandparents, Annie Scanlon from county Mayo and George Mawer, a private in the 50th Regiment of Foot, when he completes their story which takes up the remainder of the novel. Beginning with their marriage in Manchester Cathedral in 1847, Mawer describes the nomadic and relentless life of an ordinary soldier’s postings, the lack of privacy and of a settled home for soldiers’ families, and the difficulties faced by wives and children. When their men were sent overseas, they were no longer considered to be of any concern to the army. Left to fend for themselves, women such as Annie did what they must to ensure their families survived. This section also focuses in some detail on the Crimean War, where George Mawer fought. This war was in some ways a foretaste of World War 1 with its use of trench warfare, artillery bombardment and heavy casualties as well as, in some instances, mismanagement and chaos caused by those in command. George Mawer’s experiences – rampant disease, hunger and malnutrition, lack of shelter (tents sent well after the troops arrived) and hypothermia, loss of comrades – are harrowing and highlight the way ordinary soldiers were treated as nothing but expendable units – cannon fodder.

Skillfully, in plain but compelling prose, the characters and their world are made real. At various points in the narrative Mawer pauses and draws aside the veil to show the reader the slim documentary foundations upon which this work of historical fiction is based: birth registrations, marriages, census data, hospital records, newspaper reports. These highlight the fact that what we are reading is a real life, that the documents show us that what has just been described did really happen. Mawer also acknowledges that it may not have happened in exactly the way he has described it. At one point he asks,

‘Is that how it was? Is that what happened? The truth is, we don’t know.‘ (p.89).

And we can never know for certain but as Simon Mawer says in his final paragraph,

‘It is only through those remaining fragments – an entry in the census, a birth or a death certificate, the occasional relic passed down through the generations – that they can be perceived. Yet they lived and loved, cried tears of pain and laughter, slept and dreamt, awoke and ultimately died. We know because those are the attributes of being human; the rest is intuition.’ (p.414)

It is this intuition that the novelist uses when he or she writes a work of fiction based on real lives, an intuition based largely on the author’s own outlook on life and personality – it is possible for two people to write of the same life, based on the same documents, yet interpret those documents differently and come up with entirely different narratives.

To my mind, Ancestry is an absolutely brilliant novel. The appearance within the text of the author with his explanations and questions heightened the sense that I was reading a plausibly imagined real life. Most of all, Ancestry passes my ultimate test of all fiction – the characters are still alive in my mind weeks after finishing the story, most especially Annie Scanlon.

Ancestry was long listed for the 2023 Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction.

A more detailed review can be read here.

Pingback: My Reading – October 2023 | Catherine Meyrick

Pingback: 2023 – A Year of Reading | Catherine Meyrick