Often we think we know our country’s history, particularly if we are only one degree of separation from those who made that history. Many people of my age had grandfathers who fought in World War One. We have some of their stories, though often highly sanitized if they were told to us as children. I would say that, until recently, I had a general grasp of the war’s chronology and Australia’s part in it but no deep understanding of what it was like for those who lived through that war, both at home and abroad.

Last year I read Bill Gammage’s classic work The Broken Years: Australian Soldiers in the Great War. It is a profoundly moving book that draws on one thousand of the letters and diaries written by Australian soldiers and held in the Australian War Memorial’s collection. The historical progress of the war is traced from beginning to end but is illuminated by the words of those who took part, allowing us to glimpse what those soldiers thought and felt.

Over the past year I have been researching World War One in Melbourne, looking at its effect on the lives of those who remained behind, women in particular. This is the first of a series of posts I will share on the detail I have discovered.

When Britain declared war on 4 August 1914, Australia, as a part of the British Empire, was also at war with Germany. Recruiting began on 10 August 1914, initially at army barracks around the country such as Victoria Barracks in Melbourne. Even before the war had started but was clearly on the horizon, Andrew Fisher then Leader of the Opposition, during an election speech in July 1914, had declared Australia’s support for Great Britain: ‘Australians will stand beside our own to help and defend her to our last man and our last shilling’. Once the war began, the Australian government undertook to provide 20,000 troops, with more to follow. These had to be volunteers as the Defence Act 1903 did not permit members of Australia’s military forces to serve in a war overseas.

The population of Australia in 1914 was just under 5 million with men making up 52%. At the start of the war ‘military age’ was defined as being 19 to 39 years. Standards were high, with men required to be 5 foot 6 inches in height with a fully expanded chest measurement of 34 inches and perfect vison. Standards were lowered as the war progressed and the supply of eager volunteers declined. In June 1915 military age was redefined as 18 to 45 years, height was dropped to 5 foot 2 inches and chest expansion to 33 inches. The height limit was further lowered in 1917 to 5 foot.

By the end of 1914 around 50,000 men had enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force. Volunteers underwent a stringent medical examination which resulted in about a third of all those who volunteered being rejected in the first year of the war. Unfilled teeth and dentures were enough to have men rejected—partial plates appear to have been acceptable as men needed ‘to have a certain number of natural teeth so that they could masticate their food in the event of breaking or losing their plates.’1 Those with the means to visit the dentist could attempt to enlist again once their teeth were fixed. Some local dentists such as Mr H M J Powell of Colac2 and J H Laws of Brunswick.3 offered to attend to problematic teeth for free, though Mr Laws limited his generosity to four recruits a week. The public was bemused by this with. ‘The question of strong, vigorous. and otherwise healthy young men being rejected on account of having some trifling defect with their teeth is not received too kindly by rejects on that score. Some assert that they are not required to bite or eat Germans, and that if they can get through the ordinary restaurant menus without being laid out, surely they would come through the ordeal in the case of the military “chicken pie”.’4 This requirement was also relaxed in early 1916.

Those of the ‘1914 men’ who survived to the war’s end stood out among the other Australian soldiers as they were the ‘fittest, strongest, and most ardent in the land’.5

Although during 1916 there was a steady decline in enlistments, still a fair proportion of volunteers were rejected. Just over two months on from this, PM Billy Hughes announced the first plebiscite for the introduction of conscription for overseas service.

Many of the initial volunteers had served in the cadets or militia units, or in previous military campaigns such as the Anglo-Boer War. Around half of those who made up the First Expeditionary Force had previous military experience. Men enlisted for a number of reasons: loyalty to Britain and to the British Empire, a sense of obligation and of duty, under and unemployment, a sense of adventure and escape from ordinary humdrum life, and a hatred of Germany. As the war progressed some men, despite their family responsibilities, felt they could not look other men in the face again if they did not go.

The decision to enlist was often a pragmatic, especially among working class and rural families. Married men with children and single men supporting a mother and siblings had to weigh up their responsibilities against the call to ‘duty’. Wives and mothers did have reservations about their men going. Some middle-class families even had reservations about their sons mixing with some of the types of men found ‘in the ranks’!6

During the period of the war, 416,809 men enlisted—38.7% of the male population aged 18 to 44 –with 330,000 men serving overseas. Approximately 4,000 men joined the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force and 2139 women served in the Australian Army Nursing Service.

Family and friends waving goodbye to volunteers on their way to the Broadmeadows military camp for training prior to overseas service.

New recruits were given a free railway ticket to the major cities to begin their basic training.

Once enlisted, training began often within days. Training camps were set up around the country. In August 1914, the main camp for training recruits in Victoria was established at rural Broadmeadows at Mornington Park, a property loaned to the government by the owner R G Wilson.

The Australasian 29 Aug 1914 p.57

Troops were taken from Victoria Barracks by train along the Broadmeadow line or marched to the Broadmeadows camp. On 18 August 1914 around 2,500 troop marched from Victoria Barracks through the city and along Sydney Road to the Camp. This was to be the route marched by the First and the Second Expeditionary Forces in their final parades before embarkation.

The soldiers the Australian Imperial Expeditionary Force marched to the enthusiastic plaudits of many thousands of spectators. It was a splendid turnout, and, the fine physique and bearing of the men won the heartiest commendations. Brass bands played lively music for the march. The route was from the Victoria Barracks, which the troops were announced to leave at 11 o’clock, but, it was not until some time later that the head of the column actually passed through the gates, and it was nearly 12 when it crossed over Prince’s Bridge. The St. Kilda road was well lined with spectators, but, the city sheets themselves were thronged with a dense crowd. As the men came into view the spectators broke into a spontaneous burst of cheering, and intermittent applause was kept up as the whole of the procession passed by. Every now and again some spectator would notice a friend in the ranks, and call him by name. A wave of the hand would be the response, and a moment later the incident would be repeated somewhere else near by. As the troops passed several business establishments the employees, evidently as the result of a pre-arranged signal, would shout a concerted farewell to some fellow-worker tramping past below.

The marching of the men, considering the short time they have been together, and the inevitable detraction from their appearance caused by the preponderance of plain-clothes, was really excellent. Two bands accompanied the column. The newly presented colors of the 58th battalion7, which were carried on route, caused a burst of enthusiasm at every point they passed.

Once clear of the city, the troops had various spells, and, coming through Royal Park, were halted for lunch. At 2.15 they entered the city of Brunswick, from which boundary at Park-street, to the northern boundary of Coburg at Gaffney’s-road, was thronged with men, women and children, who wildly cheered the troops as they marched past. Almost, every business and shop had streamers of flags hung across the verandahs. At the Brunswick Town Hall the Mayor (Cr. Millward), councillors and many prominent residents gathered with flags. and enthusiastically cheered as the force marched past the South African soldiers’ memorial, which had been decorated with the colors. From one side or the road to the other lines were hung with the flags of the allies and a large Australian flag almost covered the front of the municipal buildings. It is estimated that there were fully 12,000 people who witnessed the march in the two municipalities.

The Moreland and Coburg school children, who were stationed on the sideways with the miniature flags and patriotic bunting, made a bright spectacle, which will long be remembered. Fortunately, the weather was ideal for marching conditions, and the ordinarily trying journey was not marked by much discomfort among the men. As far as could be ascertained in the evening there were very few cases of sore feet among the men.

It was well on in the afternoon before Broadmeadows was reached. The men came into camp weary, but in good fettle, and satisfied that the first stage of their ‘great adventure’ had actually and satisfactorily begun.8

Once at the camp, training began in earnest…

This film from 1914 shows enlistees arriving in civilian clothing at at Broadmeadows Camp. It also gives a good idea of the range of activities and life in the camp in those early months.

My next post on World War One will look at life in the Broadmeadows camp.

A number of members of my family served at Gallipoli. All survived that campaign but not all survived the war.

Albert Reader, Thomas McGrath, and possibly Stephen Doran were part of the initial landing on 25 April 1915.

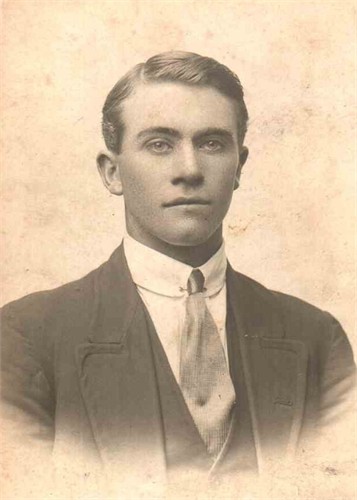

1888-1917

Enlisted: 17 Aug 1914

Embarked: 20 Oct 1914

KIA: 15 Apr 1917 Lignicourt, France

1894-1918

Enlisted: 12 Sep 1914

Embarked: 20 Oct 1914

Died: 18 Mar 1918, Middlesex War Hospital, Herefordshire

1892-1956

Enlisted: 8 Dec 1914

Embarked: 19 Feb 1915

1895-1960

Enlisted: 16 Feb 1915

Embarked: 15 Apr 1915

References

- ‘Soldiers Teeth’ Geelong Advertiser Mon 21 Jun 1915 p.3 ↩︎

- ‘Dental’ Colac Reformer Thu 3 Sep 191 p.3 ↩︎

- ‘Recruits teeth troubles’ The Brunswick and Coburg Leader Fri 30 Jul 1915 p.1 ↩︎

- ‘Rejecting recruits on account of teeth defects’ The Brunswick and Coburg Leader Fri 18 Jun 1915 p.1 ↩︎

- Gammage, Bill: The Broken Years: Australian Soldiers in the Great War, illustrated edition Penguin 1990, p.8 ↩︎

- Ziino, B. ‘Eligible men: men, families and masculine duty in Great War Australia’. History Australia, 14(2), 202–217. 2017 ↩︎

- Melbourne’s 58th Infantry Battalion was the “Essendon, Coburg, Brunswick Regiment” and part of the Citizens Military Force also known as the Militia. ↩︎

- ‘The War’ Brunswick and Coburg Star Fri 21 Aug 1914 p.2 ↩︎

This is a great post.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Barbara. I’m hoping to post every couple of months about what it was like for people home here during World War 1. There is so much information about military movements but not what it was like for ordinary people.

LikeLike