Christmas 1914 is remembered mainly as the first of World War 1, and for the Christmas Truce on the Western Front when British and German soldiers met in No Man’s Land and exchanged gifts, and even played games of football.

As part of the British Empire, Australia too was at war but had not yet begun to truly count the human cost of war. There had been casualties as a result of Australia’s first actions of the war. Able Seaman Bill Williams and Capt. Brian Pockley died on 11 Sep 1914 during action searching for and seizing German radio stations operating in German New Guinea and the islands of the Bismarck Archipelago. Six days later the HMA Submarine AE1 sank without a trace off Neulauenburg, north-east of New Guinea, with the loss of all thirty-five submariners on board. Four men died on 9 November 1914, when the HMAS Sydney disabled and seized the SMS Emden in the Battle of Cocos. The Sydney was part of the escort for the convoy of Australian and New Zealand troops enroute to England.

These men were mourned and their actions lauded by the nation; however, there was not the great depth of sorrow felt nationally as there was for the tens of thousands of deaths that would followed from 25 April 1915.

By the end of 1914 enlistments totalled 52,561 men out of a population of just over 4.9 million (approximately 50 per cent of the total male population aged between 18 and 44 at that point). Around 21,000 had left with the First Expeditionary Force from Western Australia on 1 November 1914; they celebrated Christmas in Egypt where they had landed in early December 1914, having been diverted en route. 11,000 men had left with the Second Expeditionary Force and were sailing across the Great Australian Bight when Christmas arrived. The remainder were in training camps around the country.

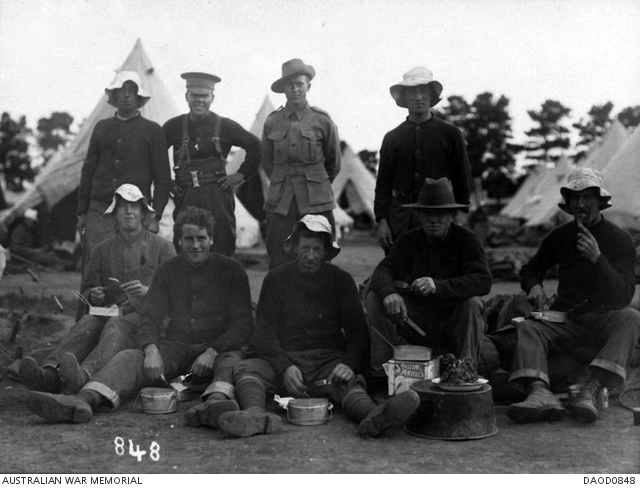

Christmas in Camp

The army was no more generous with provision for Christmas than it was in its supply of anything more than basic clothing and other requisites. The military authorities had no intention of supplementing rations for Christmas or of granting leave to more than the usual ten per cent of the recruits; however, in the matter of leave they relented and half the troops were permitted four days leave for Christmas and the reminder allowed four days at New Year.

The public stepped into the breach in the matter of rations. In the days leading up to Christmas hampers, and parcels containing turkeys and puddings arrived at the camp, donated by family, friends and members of the public. The soldiers themselves were also able to buy ‘extra dainties’. The camp was open to the public after 4 p.m. (the usual weekday time) so family members could visit those without leave. (The Age Thu 24 Dec 1914 p.7)

True to reputation, Melbourne’s weather was uncooperative on Christmas Day. Just before midday a windstorm swept down on the Broadmeadows Camp, leaving chaos in its wake. Smaller tents were uprooted and even the marquee that was used as a reading room and meeting hall was partly wrecked. And then came the rain. The men ended up eating their lunch in damp tents but they ‘accepted the trying conditions in a cheerful spirit, and by sundown the camp was again snug and tidy.’ The weather also meant that most of the expected visitors stayed at home. So, the men amused themselves with sing-songs and an early night. (The Age Sat 26 Dec 1914 p.10) The only highlight of the Christmas period was the heavy load of mail received at the Camp’s Post Office.

Christmas at Sea

Trooper C R L Halloran of the 2nd Light Horse Regiment spent Christmas aboard HMAT Seuvic. In a letter home in early 1915, he wrote about the food in general as well as at Christmas.

There is always tea, porridge (with sugar and milk), bread and butter, and meat. At midday there is soup, meat, and vegetables, with sometimes pudding instead of the soup.

On Sunday, at midday, we have been getting soup, meat, vegetables, and pudding. We had thought they might give us something a bit out of the ordinary on Christmas Day, and they did too. It was not as good a Christmas dinner as some of the men would have had back home in sunny New South, but what man could grumble when he saw the mess orderlies staggering down the troop deck stairways with soup, roast fowl, roast pork, boiled potatoes, green peas, and steaming able-bodied plum puddings? The usual food for the evening meal is bread, butter, and jam. Sometimes there is also brawn or some other kind of cold meat, and when there Is there are pickles to match it.

The tea on Christmas night was deserving of two appetites a man. There were cold fowl, pork, and vegetables left over from dinner, in some instances, also pudding. The usual bread, butter, and jam were issued, and there were mince cakes in plenty as an added luxury. To cap all, for A squadron of the 6th Regiment, anyway, there was the huge cake presented to the squadron by Lieutenant A. R. (Roy) Hordern, who commands D troop. I don’t know what it weighted, but it took two strong men to carry it in its box. It was two feet across at the base and about three feet high. A gorgeous iced affair it was, with an iced kangaroo on top and iced cherubs pursuing each other seraphically among colored Union Jacks around the desirable sides. It worked out at a good, solid slice a man, and each participant was duly grateful to Lieutenant Hordern. This officer also had a pipe and a tin of tobacco presented to each member of his troop as a Christmas gift.

The Argus ‘Correspondent with the Forces’ was also on board the Ulysses, the flagship of the 2nd Australian Contingent, and describes something similar.

Church parades were conducted on the ships. On the Ulysses, the Presbyterian chaplain, Captain A. Gillison, conducted two services for the protestants on the quarter-deck, one for the 13th Battalion and one for the 14th. Both involved a sermon and ended with the singing of the National Anthem. There was no Catholic chaplain on the Ulysses but a service was conducted by an officer, Captain J. N. Edwards, of C Company of the 13th Battalion. He read the prayers of the Mass, and gave a brief address. The troops sang the Te Deum and the Litany.

The men on board formed a large choir in the evening and with hymn books at hand the choir ‘sang itself hoarse’.

The Christmas 1914 Church parade would have been similar.

The Argus Correspondent also reported that some of the men exchanged gifts bought from the dry canteen such as cigarettes and sweets. The representative of the Young Men’s Christian Association sailing with them, Mr L. Hanlin, gave each soldier a small packet of active service post-cards as a Christmas gift, which were put to immediate use with many writing home. (The Argus Wed 3 Feb 1915 p.9)

Private George R. Clapham of the 14th Battalion, was also aboard, H.M.A.T. Ulysses. In a letter home he described his Christmas dinner differently—

Christmas Day was spent in the Bight. We had [plum]duff for dinner—that was the only way of noting any difference. I would have liked to have been home for Christmas; but it was not to be.

Perhaps he was used to better things. Two days later her was inoculated for typhus. On the 28th they dropped anchor in King George’s Sound off Albany but no leave was granted. On 31 December 1914 the convoy steamed out, leaving Australia behind. (Gippsland Mercury Tue 13 Apr 1915 p.3)

Christmas in Egypt

The members of the First Expeditionary force had been in Egypt several weeks, encamped at Mena Camp on the western outskirts of Cairo, and by Christmas knew their way around. They were comparatively well paid, resourceful and intent on making the most of their time as can be seen from the following reports and letters. Most seem to have been able to supplement army rations and spent part of the day sightseeing in various ways.

The Correspondent for Sydney’s Daily Telegraph, wrote on 27 Dec 1914 describing the Christmas activities of the men.

Christmas, 1914 will live in the memory of the oldest inhabitant of Cairo as the merriest and brightest on record. The city was literally packed with soldiers determined to enjoy themselves to their heart’s content. They filled the best restaurants and cafes, and places of amusement, and surged in an unbroken stream through the main streets…

On Thursday and Friday afternoons all sorts of conveyances were requisitioned to deal with the throng of pleasure-seekers from Mena and Heliopolis. Taxis and motor cars, as many as ten and twelve men in each, were most favored. Others rode camels at the risk of becoming ‘seasick’, while scores more mounted on donkeys, the riders, using their swagger sticks to good purpose. … Scores of men returning to camp on Christmas Eve carried turkeys, geese, and ducks in their arms. These were duly decapitated and handed over to the cooks. On Christmas Day each man of the 3rd Battalion was supplied with a small plum pudding, and three bottles of wine—a fairly good claret—were issued to each section. The intention was to supply beer, but it was discovered just in time that the stocks of this agreeable commodity were by no means equal to the demand. As I write, no beer is available at any of the canteens in camp, and some 18,000 men must perforce fall back on water or a very Inferior kind of lemonade.

In consequence of the holidays, stringent measures have to be taken with men overstaying leave or breaking camp; while Shepheard’s and the Continental, the two leading hotels, have been placed out of bounds. The camp has been transformed into a kind of miniature Zoo. The men have been bringing out young pet rabbits, white rats, ferrets, and canaries, with an occasional mongoose and monkey. All the pets are well cared for. (The Daily Telegraph Wed 27 Jan 1915 p.10)

Private Ernest Hazeldine, of the Military Postal Corp, in a letter to his father in Murtoa showed what could be done with a bit of ingenuity when the men worked together.

The Northam Advertiser (Western Australia) published an article by ‘E.J.R.’ on Sat 23 Jan 1915 (p.3) describing the Christmas just spent by some local soldiers.

As far as the actual celebration of the various customs which go to make up and are inseparable from an Australian Christmas is concerned, the majority of the members of the Australian Force will set down the Xmas of 1914 as an exceedingly quiet one—if not the quietest they have ever spent. The only concessions from the daily routine of the camp to mark the season were the cancellation of most of the duties on Xmas Day, and a slight relaxation in the discipline of the camp for a couple of days. No additional leave of absence was granted, but the cancellation of the daily parades gave the men an opportunity to take ‘French leave’, an opportunity which the Northam boys at least were not slow to take full advantage of. Of course a trip into Cairo was almost without exception the objective of the leave, and the absence of the customary Australian festivities were almost forgotten amidst the many absorbing and interesting scenes to be met with in a large city of the ‘near East’. I, myself, was fortunate enough to spend a considerable portion of Christmas eve, Xmas Day and Boxing Day roaming about Cairo and its environs, so had a good opportunity of seeing a Xmas in Egypt. As before stated, almost all of the customs inseparable from an Australian Xmas were absent, and outside an old cafe or two where a number of Australians foregathered to celebrate in the good old way, there was not much in the city itself to indicate that the days were more than ordinary one. Some of the large business houses were brilliantly illuminated, and an odd Xmas tree or two was occasionally seen in the windows…

Christmas Eve I spent roaming through the streets, all of which were thronged with a merry and cosmopolitan crowd. In the main thoroughfares every second person wore khaki, for every man of the English and Australian troops who could manage it, was in to do the town. The coming of the Australian troops to Cairo must be fully recompensing the business people for the falling off of the large winter tourist trade occasioned by the war…

On Christmas Day we had Church parade at 9.15, and at 11 o’clock 20 per cent of the men were granted leave, and about 75 per cent of the remainder took it. Special rations of cake, rice, raisins and preserved fruit were issued; but many of the men went into Cairo to have a good fat dinner. In the afternoon the Cairo Zoological Gardens attracted many of the troops, and those who visited them could not help, but be pleased with what they saw. Amongst the animals the most interesting were the giraffes, lions, antelopes, gazelles and monkeys. The greatest charm of the gardens, however, was not in the collection of animals, but in the artistic landscape gardening and splendid footwalks. The large shady ornamental trees, winding-pools and rustic bridges; the grottoes handsome suspension bridges and terraces make the gardens a thing of beauty.

at Mena Camp on Christmas Day 1914.

Not everyone had a good Christmas.

Another Western Australian soldier (unnamed) whose letter home was published in the Boulder Evening Star (Sat 30 Jan 1915 p.1) was unimpressed with the food generally and with Christmas in particular.

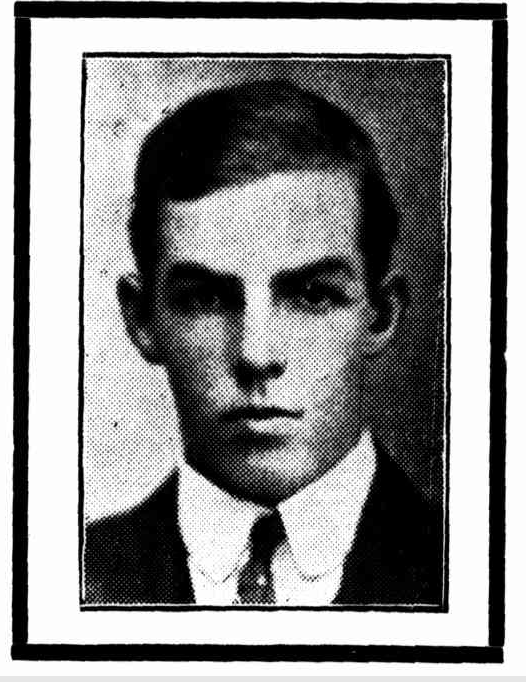

Private Percy Leo Michelly was not enjoying himself either. His concern about letters from home seems to indicate a degree of homesickness. He also appears to have been a diligent young man – not given leave he stayed on in an almost deserted camp.

Thu 18 Feb 1915 p.5

While many soldiers appear to have made the most of their Christmas Day and the opportunity to experience the unfamiliar sights and experiences of Egypt, others were clearly missing home. For all those who survived to eventually return home, it was part of an experience that altered the course of their lives.

Soldiers mentioned in this post

Trooper Clifford Robert Lang Halloran died in the No.19 General Hospital, Alexandria, on 7 Sep 1915 of shrapnel wounds to the abdomen received at Gallipoli on 4 Aug 1915. He was buried at Chatby cemetery, Alexandria. He was a reporter prior to enlistment and was 22 years old.

Photograph from: The St George Call Sat 23 Oct 1915 p.1

Private George Roy Clapham was killed in action at Gallipoli on 13 Sep 1915 and was buried at Lower Cheshire Bridge on the same day. He was an engine driver prior to enlistment and was 21 years old.

Photograph from: The Age Sat 6 May 1916 p.18

E.J.R. was most probably Private Edward John Richards a 29 year old journalist at time of enlistment. He was invalided back to Australia per Ulysses in January 1916 suffering from Enteric Fever. He joined the Australian Flying Corps as a Lieutenant in October 1916 and embarked on the Themistocles in August 1917. He served in England and France and returned to Australia on the Kaiser-i-Hind on 9 Jun 1919.

Private Ernest Samuel Hazeldine rose to the rank of captain in the Military Postal Corps. His only injury seems to have been an attack of appendicitis in 1916. He returned to Australia on the Orontes on 21 Feb 1920. At time of enlistment, he was a 27 year old mechanic.

Private Percy Leo Michelly of the 7th Battalion was invalided home to Australia on the Seang Choon on 7 July 1916 suffering from double inguinal hernias He was a 21 year old grocer at time of enlistment.

A compelling read, Catherine.

It seems almost inappropriate – but a very Merry Christmas and happy New Year to you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Mike.

Best wishes for 2025, definitely hoping it’s an improvement on this year.

LikeLike

Pingback: Australia Will Be There | Catherine Meyrick