Margaret Horgan was born in Cork in 1837 and baptized at St Mary’s Cathedral on 14 May 1837. She was the eldest daughter of Patrick Horgan and Ann Connelly, the second of their six children.

Patrick was a ropemaker for the Royal Navy. He and Ann had married in the same church on 30 May 1834. The family lived at Malt-House Lane, off Peacock Lane (now called Gerald Griffin Avenue and a less avenue-like street I have not seen). Nothing is known of Margaret’s life before she left Ireland in 1854 except that she was not in service but had been at home with her mother.

Malt House Lane was probably like this.

Margaret arrived in Hobart Town, on board the Duchess of Northumberland on 6 December 1854. On the passenger list, Margaret’s surname was recorded as Horigan. Although Margaret could read, she could not write, and the spelling might have something to do with her accent and what the shipping clerks thought they heard. Her younger brother James Joseph joined the Royal Navy in 1856 aged 15. Although he could read and write, his name changed on naval records over the years from Horgan to Horgans, to Horegans to finally Horigan.

Margaret was an assisted immigrant, having paid paid £3 of the £13 fare. She had travelled with her 24-year-old cousin, Eliza Connelly, on the four-month journey. The arrival of the Duchess of Northumberland was greeted positively by the Colonial Times (7 Dec 1954 p.2)—

The Duchess of Northumberland, barque, which arrived yesterday from Plymouth, brings, in all, 255 souls, viz., 103 single girls, 14 single men, 40 married couples, 52 boys and girls, under 14 years, and 8 children under 1 year. The immigrants, with the exception of three English girls, are Irish, and are a healthy looking superior class, especially the single females.

On 15 December Eliza Connelly1 was hired as a nursemaid by Mrs Swan, most probably the wife or daughter-in -law of John Swan of Beaulieu, New Town Road, a wealthy Hobart merchant. On the Duchess of Northumberland’s list of immigrants, she was described as a general servant and a nursemaid. Just over a week later Margaret was also hired as a nursemaid by Mrs Swan for a period of twelve months. She was described as a child’s maid and good at needlework in the list of immigrants. On 16 March 1857, just over two years later, Margaret married 32-year old, Isaac Merrick at St George’s Church, Battery Point.

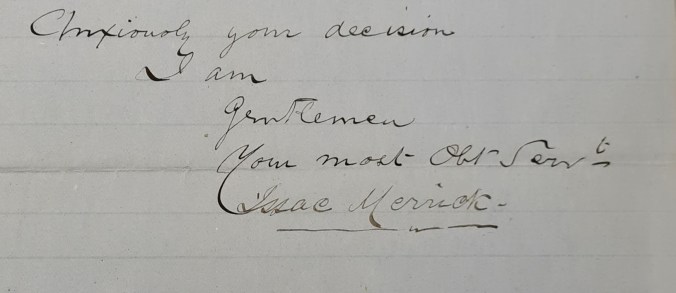

Isaac2 was born in Milson, Shropshire in 1826, the third son and seventh child of Thomas Merrick and Elizabeth Clark. By 1834 the family had moved to industrial Walsall in Staffordshire where Thomas, formerly a canal navigator (a canal labourer – the original navvies), was working as an ironstone miner. On 4 November 1843, aged 17, Isaac was committed to the Stafford Gaol and charged with the theft of a bag containing the sum of £1 1s 6d, the property of the town council of the Borough of Walsall. He was tried on 4 January 1844 and, although this was his first offence, he was sentenced to seven years transportation to Van Diemen’s Land. After a period in Millbank Prison, he sailed on the second voyage of the Marion as a convict transport, arriving in Hobart Town on 16 September 1845. He received his Ticket of Leave on 1 December 1846 but in May 1849 he, with another Ticket of Leave holder, took part in a burglary for which he received a sentence of fourteen years, the first twelve months were spent at Port Arthur. Eventually, on 6 February 1855 he received his Ticket of Leave again and on 16 September 1856, Isaac received a Conditional Pardon. He married Margaret six months later.

Margaret and Isaac had twelve children between 1858 and 1880. They moved house quite frequently around Hobart during the first twenty years of their marriage, and Isaac had a range of occupations: tailor, gardener, milkman, laborer, farmer and shopkeeper. Their first child was John Edward born in 1858, followed by Thomas in 1860, Elizabeth Ann in 1861, Margaret in 1863, Isaac Joseph in 1865, James Michael in 1867, Elizabeth Jane (later known as Mary Jane) in 1869 and Emma Elizabeth in 1871. All the children, except John Edward were baptised either at St Joseph’s Catholic Church or, once it was opened, at St Mary’s Cathedral. I have been unable to locate a baptismal record for John Edward. Sadly, in 1864, when the family was living at New Town, Elizabeth Ann, now aged two years and five months, died of convulsions.

Courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales.

By 1868 Isaac and Margaret were living at 306 Liverpool street where Isaac was running a shop. They were to stay there until 1872. On 4 January 1870, the Royal Navy’s Flying Squadron, which was circumnavigated the globe, arrived in Hobart. The Flying Squadron was an experiment in efficiency by the Admiralty, thinking that one or two flying squadrons of half a dozen or so ships might be more economical than a dozen permanent squadrons based around the world. On board one of the ships in this fleet, HMS Liverpool, was Margaret’s brother James Joseph Horigan, a Gunner’s Mate. It is comforting to think that even though Margaret had moved to the other side of the world, she did get to see a family member. The contact must have continued too as my father said, when he was a child, that there was a photograph on display in his parents’ house of James Horigan in the uniform of a naval Lieutenant, his rank upon retirement in 1896.

Unfortunately, Isaac was not able to make a success of the shop. Faced with mounting debts, he gave it up and moved his family to Bruny Island in 1872 where he was one of a number of assistants to the Lighthouse Keeper, John Scott. Margaret and Isaac’s daughter Christina was born there in November 1872 and another son, Gabriel Charles, in October 1874. Neither of these births were registered but both were baptized at St Mary’s Catholic Cathedral.

Life did not go well for Margaret and Isaac on Bruny Island. Their living conditions appear to have been basic, with the family of ten living in what was described as a ‘hut’. The lighthouse on Bruny Island is at the south of the island (latitude 43°29’22.3″S – within the Roaring Forties) distant from the settled areas on the island. And although the view from the lighthouse is stunning on a sunny day, Margaret possibly felt isolated. Not only had she lived all her life to this point in a city with people always around her, but she may have been the only woman at the lighthouse at that time, other than the Lighthouse Keeper John Scott’s wife and daughters.

John Scott, appears not to have been the easiest man to get along with. The Parks Tasmania website (accessed in 2009) said the following—

John Scott’s (Superintendent, 1863-76) relationships with his staff were fraught and highlight the difficulties inherent in operating Tasmania’s remote lightstations. Teamwork between superintendents, assistants and their families was essential to ensure a harmonious and efficient station. Extended periods of rigidly hierarchical life in these tiny and remote communities tested the most phlegmatic of souls. In November 1871 Scott was calling for the dismissal of assistant keeper Thomas Winter saying, “I cannot have this man here, it appears to me he has come here on purpose to annoy me it is impossible for me to have any control over such a violent tempered man, therefore I humbly beg you will release me of him.”

By 1875 he was calling for Isaac’s dismissal.

Isaac wrote to the Marine Board in Hobart on 14 March 1875 complaining about his conditions and Scott’s behaviour towards him. A week and a half later, Isaac and Margaret’s youngest daughter Christina choked to death on a piece of raw turnip. An inquest had to be held but, because of the choppy seas, the Coroner wanted Christina’s body brought to the mainland. Isaac argued with Scott and refused to let Christina be taken away which led to Scott, rather than taking a more placatory approach with a grieving man, threatened Isaac, saying that he would get the constable to remove him from the island. Margaret, naturally, was very upset, Scott describes her has getting ‘in a great passion’ because Scott’s wife could not provide her with a bottle of Brandy. Scott said, ‘We done all we could to assist them notwithstanding his bad behaviour’. This included providing the wood and assisting with making the coffin. Surely, any person out of common humanity, would have done as much – did he expect Isaac to do this himself? He also claimed that Mrs Scott had made a dress to bury Christina in because Margaret did not know how to, which is a very odd claim considering Margaret was described as being good at needlework.3

Christina was buried on Bruny Island. On my visit to Bruny Island some time ago, I did not have time to visit her grave but I was told by the guide at the lighthouse that it is down near the beach, below where the keeper’s house and the assistants’ huts were. He said it was very beautiful place.

Courtesy ‘Find a Grave’ website.

Four days after Christina’s death, Scott wrote to the Marine Board asking for Isaac to be removed. He described Isaac as a ‘lazy skulker’ and insolent. He said Margaret and John, the eldest son, were insolent too. He accused the Merrick children of running ‘about the bush doing mischief’. Isaac disputed Scott’s reports with his own claims, not least that Scott wasn’t fulfilling his duties, rarely inspecting the lighthouse, and did not provide the men with adequate soap or clean rags to clean the lights. He also mentioned that Scott’s daughters thought they could go in and out of his family’s hut at will, and when challenged by one of his sons, one of the daughters hit him on the hand with a stick. Isaac also wrote of an occasion where ‘my daughter was out with the baby when she was assaulted by the Misses Scott, one taking hold of her, and the other saying she would ride her down, being on horseback’.

Despite this, Isaac’s employment was terminated. The order for removal came when Isaac had gone to Hobart to get treatment for a bite from one of Scott’s dogs. Scott went to Margaret and said that ‘he had orders for our removal, and that she and my family and goods must be off at once’.

That threat must have been deeply distressing for Margaret, still grieving, without her husband’s presence. It seems, though, that this was just cruel bluster on Scott’s part. Margaret appears to have been a woman who could stand her ground; during Scott’s attempt to remove Christina’s body to the mainland, Margaret called him ‘a bad and wicked man’ to his face.

It is pleasing to note that John Scott was investigated by the Marine Board and removed from his position in mid-1876, though he was given the courtesy of three months to organize his departure from Bruny Island.

So Margaret and Isaac moved back to Hobart, initially to a small, possibly run down, house in Riley’s Lane on Old Wharf and then at 23 James Street/Cottage Green, Battery Point. From there they moved to the George’s Bay area with another daughter, Virginia, born at Fingal in July 1877. By this time Isaac was working as a carter. The family finally settled at St Helens where Isaac rented a cottage and nine acres of land. Two years later he bought eight acres where the family lived for the next twenty years. Isaac took up tin mining, an occupation that all but one of his sons were to follow in.

Finally at St Helens, a growing town with the discovery of tin, they had a home of their own and Isaac was his own boss. But Fate in its crueller aspect had not done with Margaret and Isaac. On 5 November 1878 Isaac was driving a dray loaded with tin, his thirteen-year-old son, Isaac Joseph, riding on the back. Somehow, young Isaac slipped off the dray and before he could right himself the wheel ran over the upper part of his body and his neck. The inquest, held the next day at the Telegraph Hotel St Helens, returned a verdict of accidental death and said that the death would have been instant. Isaac Joseph is buried in the church yard of St Stanislaus Church, St Helens. His grave has a headstone that reads

IN

Loving Memory of

ISAAC JOSEPH MERRICK

Accidentally killed Nov 5, 1887(sic)

aged 13 years

R.I.P.

The hand holding a cross at the top of the headstone is said to symbolize the hope of the resurrection, the lilies innocence and purity.

Two years later, almost to the day, Margaret and Isaac’s last child was born, a daughter Frances Honorina (later known for a time as Honorina Beatrix Eugenia). From then life seemed quiet for Margaret and her family. In 1888, her eldest daughter Margaret married a widower, ‘Godfrey’ Becker, at Ringarooma, then in 1892 Mary Jane married Matthew Hartnett, a legal clerk, at St Helens . Another three years on, at the end of 1895, their eldest son John Edward, a tin miner like his father, married Bridget Brannigan at Fingal. After marrying they lived at St Helens. Margaret and Isaac’s youngest son, Gabriel Charles married Julia Olive Maude Sales at North East Dundas on the West Coast in 1897.

In that year, misfortune struck again. While waiting up for his sons to come home, Isaac dozed off on the sofa. Woken by the smoke, he found the roof near the chimney ablaze and only had time to make sure Margaret and their daughters were out of the house before the whole house went up. By this stage Isaac was seventy-one and Margaret was sixty. They didn’t rebuild but moved instead to Alberton where their daughter Margaret was living.

On 1 January 1901, the new century began, the disparate states federated to become the Commonwealth of Australia and two of their children married. James Michael, a miner, married Blanche Harriett Becker at Mathinna and Honorina Beatrix Eugenia married Phillip Becker, also a miner, at the same place. I don’t know if it was a double ceremony but Blanche and Phillip were brother and sister and children of ‘Godfrey’ Becker, husband of James and Honorina’s sister Margaret. In May of 1900, Emma Eliza Merrick married John Birchill Fenner, a miner, at Launceston. All ended up living at Alberton. James’s wife Harriet died of complications of childbirth a year later; their son, James Lawrence only lived for four months. James never remarried.

Children of John Edward Merrick & Bridget Brannigan

John Stanislaus (Stan – my grandfather), Bertha Mary, Helen Grace & William Isaac (at front).

Isaac died on 26 January 1904 and was described as ‘much respected during his long residence in the state’, his convict beginnings hidden by time. Margaret stayed at Ringarooma, living with her son James; most of her children were not too far away, only four or five miles, at Alberton or at St Helens. Only Gabriel was distant, living on the other side of the state. As well as having her children near, Margaret had a growing number of grandchildren, thirty-eight in all by 1922 when the last one was born.

Margaret died at the Launceston Public Hospital, her daughter Virginia at her side, on 12 April 1924, following a fall at home.

Sincere regret was expressed when it became known that Mrs Margaret Merrick, who had the misfortune to break her leg, had passed peacefully away in the Launceston General Hospital on Thursday night last at the great age of 86 years. Mrs Merrick leaves a large grown up family to mourn their loss. She had been an invalid for many years. Deceased had resided with her son and daughter for a number of years. Mrs Merrick was greatly respected by all who knew her and was noted for many acts of kindness. The funeral took place in Launceston on Saturday morning, the interment taking place at the Carr Villa cemetery and was well attended. The Rev. Father Adulum officiated at the grave.

Daily Telegraph Wed 16 Apr 1924 p.2

When a life is told quickly it is easy to miss the struggles, the sorrows and the joys. Margaret’s life could be summarized as that of a young woman who emigrated from Ireland, married a little over two years after arriving, lived in Hobart for twenty years, had twelve children, three of whom died (but that happened a lot in those days) and, after a couple of years on Bruny Island, finally settled at St Helens and lived on to a great old age. Listing names and dates and rattling off a life like that offers no real insight or understanding of the reality of Margaret’s life. Instead we need to pause at each of those moments of Margaret’s life and imagine. Think what it was to be seventeen years old, leaving your family behind to travel half way around the world in a crowded sailing ship; to marry without your family to assess and welcome the man you would spend the next forty or fifty years with; to pack up and move your home every couple of years, always with one more baby demanding your attention; to worry about putting food on the table as your husband changes jobs almost as often as you move house. Imagine the unreality, the heart-tearing grief in those moments when Margaret held the bodies of her three children, dead long before their time. See her standing in the dark, watching her home burn down with all in it including, perhaps, treasured mementos of the family she left fifty years before. And recognize the stoicism, the endurance, the courage it took as Margaret squared her shoulders and went on.

This is Women’s History Month when we acknowledge the lives and achievements of women who have broken barriers and done great things in all the fields of human achievement. These women deserve that celebration but we should never forget the ordinary women of the past. They, women like Margaret Horigan, are the silent ones. They left behind no writings, the words they spoke are lost with time, yet it is through their struggles and the courage of their everyday lives that we are here today, most of us living better and freer lives than they ever dreamt possible.

__________________________________________________________________________

- By 1860 Eliza was in Launceston when she married Joseph Harman at St Joseph’s Church. Joseph was a farmer and the family lived in the Kentish area. ↩︎

- I will, at a later date, examine Isaac’s life in greater detail. ↩︎

- All information and quotations concerning Isaac and Margaret’s time on Bruny Island come from the file held by the Tasmanian Archives MB2/5/1/26 – Bruny Island 1 Jan 1872 to 31 Dec 1882 part of MB2/5 Correspondence with, and returns and reports from, lighthouse keepers. ↩︎

__________________________________________________________________________

©Catherine Anne Merrick.

Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Catherine Anne Merrick and https://catherinemeyrick.com/ with appropriate and specific direction and links to the original content.

A poignant tale that put our own lives into context.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It does. It’s good to be reminded, now and again, how fortunate we are.

LikeLiked by 1 person